This person wrote an awful lot about the Apple/FBI issue without, apparently, bothering to learn the first thing about it.

The FBI had requested Apple to give them a special version of iOS with weakened security features so they could attempt to brute-force the passcode. If Apple had complied, the FBI (and anyone else who got their grubby hands on it, which you can bet woukld be pretty close to “everybody”) could have used it on ANY iPhone.

Apple was absolutely right to deny this request. And yes, secure communication saves lives, all over the world. Why is that surprising?

That was my take too. Their overall point wasn’t bad but the start was a complete non sequitur that made me question if I wanted to finish because it’s a bad foundation for their actual argument.

I gave up when they randomly jumped topics and I couldn’t tell how they were related. And just generally felt like this essay could have been heavily edited to get it’s point across.

In general I like the EFF and the ACLU, but I do think that it’s not uncommon for them to end up on the “wrong” side because they extrapolate too far or are being dogmatic when most things have and require nuance.

The EFF believes every slope is very, very, very slippery indeed.

Many of them aren’t that slippery. Cleaving absolutely to a hard rule is just walking away from the hard work of good governance. I wish they’d focus way more on privacy and competitive goals like adversarial interoperability and a lot less on speech because they often have an approach to speech that makes me a little gag-y.

It’s funny, because the first time I heard an academic type seriously talking critically about the idea of free speech being an unfettered and absolute right was on the EFF’s own podcast. Pointing out that we as a society have all kinds of very real limits on speech that nearly no one thinks of as at all controversial (e.g., anti-defamation rules, sexual harassment bans, or all kinds of conspiracy/incitement statues). Yet they then come and make statements like they did about the KiwiFarms case where the threat they believe in is just so overstated.

I think it’s a lot rarer for the ACLU to have me raising my eyebrows. To me, they feel a lot more steadfast and predictable. The ACLU will defend a LOT of genuine criminals, but they do so because we factually live in a police state propped up by repeated anti-civil rights SCOTUS opinions. They do so because the outcomes of those cases WILL affect innocent people in a straight line – the police WILL take every opportunity to violate you without a second thought even if it ISN’T allowed, and will do so with gusto when it is. I don’t think there is a similar straight line with a Tier 1 ISP killing traffic to a known hate site that regularly threatens and incites violence against specific people.

The ACLU tends to rabidly support anything that labels itself as free speech, even if it actually stifles it. Most importantly, to me, their continued support for Citizens United.

But maybe that’s the only real case and it’s just loomed so large in my mind for the chilling impact “corporations get free speech, and their dollars count as that” has had on the US political landscape.

I never really thought about them defending that bullshit, but that’s worthy of heavy criticism.

Any time you find yourself on the same side of an issue as the Cato Institute, you should think real long and hard about your position.

At least, not at first. As the scandal heated up, EFF took an impassive stance. In a blog post, an EFF staffer named Donna Wentworth acknowledged that a contentious debate was brewing around Google’s new email service. But Wentworth took an optimistic wait-and-see attitude—and counseled EFF’s supporters to go and do likewise. “We’re still figuring that out,” she wrote of the privacy question, conceding that Google’s plans are “raising concerns about privacy” in some quarters. But mostly, she downplayed the issue, offering a “reassuring quote” from a Google executive about how the company wouldn’t keep record of keywords that appeared in emails. Keywords? That seemed very much like a moot point, given that the company had the entire emails in their possession and, according to the contract required to sign up, could do whatever it wanted with the information those emails contained. EFF continued to talk down the scandal and praised Google for being responsive to its critics, but the issue continued to snowball. A few weeks after Gmail’s official launch, California State Senator Liz Figueroa, whose district spanned a chunk of Silicon Valley, drafted a law aimed directly at Google’s emerging surveillance-based advertising business. Figueroa’s bill would have prohibited email providers like Google from reading or otherwise analyzing people’s emails for targeted ads unless they received affirmative opt-in consent from all parties involved in the conversation—a difficult-to-impossible requirement that would have effectively nipped Gmail’s business model in the bud. “Telling people that their most intimate and private email thoughts to doctors, friends, lovers, and family members are just another direct marketing commodity isn’t the way to promote e-commerce,” Figueroa explained. “At minimum, before someone’s most intimate and private thoughts are converted into a direct marketing opportunity for Google, Google should get everyone’s informed consent.”

Google saw Figueroa’s bill as a direct threat. If it passed, it would set a precedent and perhaps launch a nationwide trend to regulate other parts of the company’s growing for-profit surveillance business model. So Google did what any other huge company caught in the crosshairs of a prospective regulatory crusade does in our political system: it mounted a furious and sleazy public relations counteroffensive.

Google’s senior executives may have been fond of repeating the company’s now quaint-sounding “Don’t Be Evil” slogan, but in legislative terms, they were making evil a cottage industry. First, they assembled a team of lobbyists to influence the media and put pressure on Figueroa. Sergey Brin paid her a personal visit. Google even called in the nation’s uber-wonk, Al Gore, who had signed on as one of the company’s shadow advisers. Like some kind of cyber-age mafia don, Gore called Figueroa in for a private meeting in his suite at the San Francisco Ritz Carlton to talk some sense into her.

And here’s where EFF showed its true colors. The group published a string of blog posts and communiqués that attacked Figueroa and her bill, painting her staff as ignorant and out of their depth. Leading the publicity charge was Wentworth, who, as it turned out, would jump ship the following year for a “strategic communications” position at Google. She called the proposed legislation “poorly conceived” and “anti-Gmail” (apparently already a self-evident epithet in EFF circles). She also trotted out an influential roster of EFF experts who argued that regulating Google wouldn’t remedy privacy issues online. What was really needed, these tech savants insisted, was a renewed initiative to strengthen and pass laws that restricted the government from spying on us. In other words, EFF had no problem with corporate surveillance: companies like Google were our friends and protectors. The government—that was the bad hombre here. Focus on it.

I don’t know whether it is illegal for someone to open a letter addressed to you or not, in the country you live, but this is pretty important. If the information presented here is accurate, this is not simply EFF focusing on the government, its EFF actively resisting similar rules to be applied on e-mail as those applied on regular mail. Would anyone use any of the non-electronic mail service providers or courier services if it was a given that for each piece of mail sent, there would be exactly one open and read, shared with multiple other parties besides the sender and receiver?

It seems to me that this is the whole point of this (quite long, but interesting) article and this instance probably illustrates it better than any other chosen to discuss in the article.

That’s a lots of words to say the EFF focuses on countering government surveillance, while doing little about business surveillance.

From EFF’s About page:

Protecting Freedom Where Law and Technology Collide

…or in other words, water is wet.

Criticizing the Apple case, trying to paint Privacy Badger as an “ad blocker extension for Chrome—a browser made by Google” like somehow endorsing Google’s surveillance which it blocks (and I have it running on Firefox), or making fun of free OpenSource privacy tools and encryption… all come through as highly disingenuous attempts to discredit the EFF in order to… what? Prove that it does what it says it does?

Sure, the modern boogie man is “big corp” like Google or Facebook; that doesn’t mean the former boogie man of mass government surveillance has gone away.

PS: as I write this, and it gets federated unencrypted onto hundreds of instances all over the world, let me salute all our friendly data mining AIs —present and future— from Google, Meta, Criteo, AdRoll, QuantCast, FBI, CIA, MI5, MI6, FSB, MSS, and surely many others.

The main difference is that in the fediverse, the data is available to everyone, not just the most dangerous government organizations in the world (and hackers).

Yeah, I’m a little concerned about the potential for more advanced cyberstalking with everything so readily available, but…well it’s public, and I treat it as such. I should probably cycle and retire accounts/servers more frequently tbh. But I like it here at sdf.org…

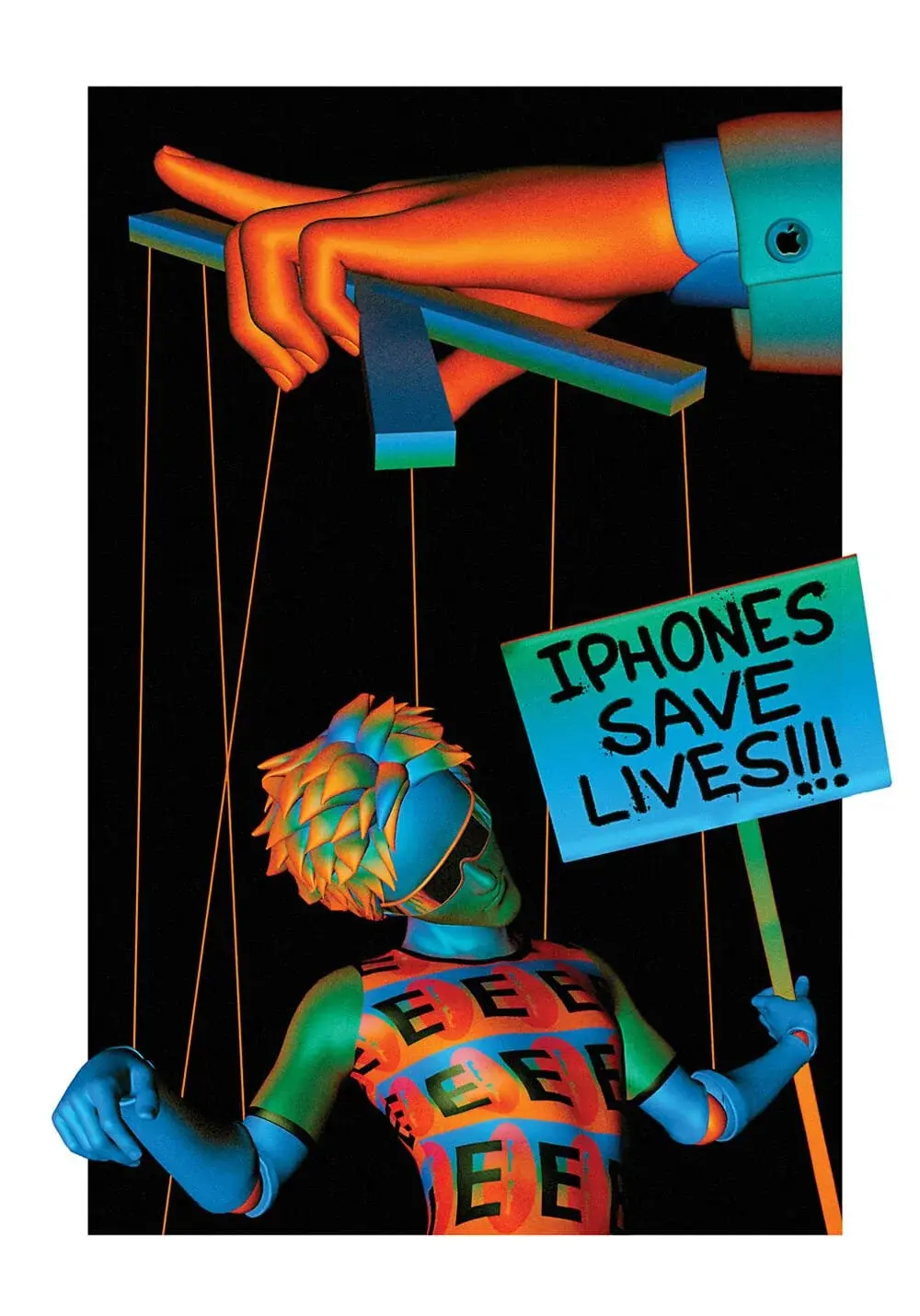

Whenever anyone reading this feels stupid or embarrassed, just remember the “protesters” standing out in the cold in support of Apple. It will make you feel better.

Protesting state surveillance sometimes aligns with… “the enemy of your enemy”, and all that.

It finally turned out the FBI could get the data anyway, so the request they made to Apple was double-sus.

My memory from the time was that the FBI probably wanted a court to grant presidence, even though they had the tools to do it anyway. Having a court order to break iPhone encryption would make state surveillance easier nationwide. Once public opinion turned and 1st amendment rights were brought into it, the FBI backed down and eventually were able to crack into the phone in the slower way (that they probably knew they’d be able to all along). And of course, 7 years later, there is no report of any information being found on that phone which lead to taking down terrorists or preventing other mass shootings.

They wanted a precedent, but one much more serious than for getting help accessing a single iPhone, they wanted a precedent to obtaining a general backdoor to access ALL phones from a given manufacturer.

Meaning, getting backdoors from all manufacturers to access every phone passing through the hands of the FBI, CIA, TSA, random cops (they all can already force you to biometrically unlock it, but not if you only use a PIN)… possibly sharing the tool with Five Eyes friends… and very likely having it leaked like the $1 TSA keys on AliExpress, available to players like the CCP, FSB, Iran, and everyone.

From there, to mandating all manufacturers to make those backdoors available from day one, or trying to pass some genius laws like in the UK or Australia, asking for the decryption keys to all encryption keys to be “deposited with a trusted authority”, or gag orders that forbid even mentioning having a gag order to introduce a backdoor… it’s not even a slippery slope, it’s just copying actual legislation already proposed or approved in friendly countries.

And it’s far from over, it’s a constant battle between the good guys wanting “just a tiny backdoor”, and reality where any broken encryption, is open to everyone, no middle grounds.